By the late 1950s Philadelphia was wrestling with an uncomfortable truth: Connie Mack Stadium, where the Phillies and other teams had played for decades, was showing its age and its neighborhood was in decline. City leaders and team owners thought a modern, larger facility would anchor development in South Philadelphia. Voters approved a bond issue in 1964 to finance a new, multipurpose stadium intended to be home to both the Phillies and the Eagles. That public backing reflected more than a love of sports. It was about keeping franchises, civic pride, and the economic activity that a big stadium promised.

Ground was broken in October 1967, but what looks simple in hindsight was messy at the time. The project ballooned in cost, and voters were asked to approve additional funding in 1967 after overruns pushed the price well past initial estimates. Weather, labor unrest, and construction setbacks pushed the opening back from the targeted 1970 debut to the spring of 1971. The Vet’s path was also clouded by scandal: reporting at the time described corruption investigations tied to stadium management that added to the delays and distrust. In all, what was supposed to be a straightforward civic project became a complicated, expensive undertaking—one that left the city with a stadium that was both awe-inspiring and long on concrete.

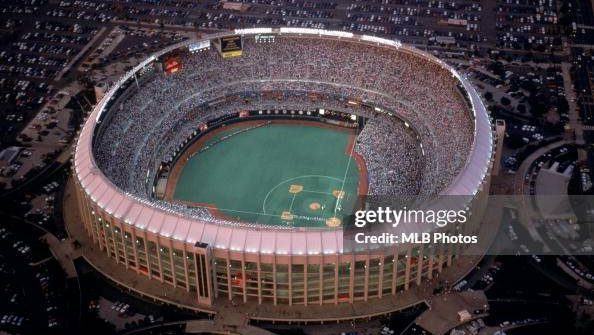

Design, capacity, and the “Field of Seams”

The stadium was designed as a true multipurpose colossus. Seating was layered in multiple stacked levels to make the bowl work for both baseball and football, and capacities topped out at more than 65,000 for football and over 61,000 for baseball in some configurations. The playing surface, however, would become an ongoing sore spot. The Vet opened with AstroTurf, and over the years the artificial surface developed gaps, seams, and hard spots. Players and agents derisively nicknamed it the “Field of Seams” and the turf’s unforgiving nature was blamed for injuries and poor play. It should be noted that various members of the Phillies who played in the stadium for long periods were later diagnosed with various cancers, although a direct link has never been proven. The rough turf and the stadium’s concrete geometry contributed to the sense that the Vet felt like a machine for events rather than a home with charm.

The jail in the basement and Eagles Court

One of the Vet’s most peculiar and very real features was its basement courtroom and holding area. After a particularly violent game and ongoing fan behavior problems in the 1980s, team and city officials worked with a judge to create an on-site judicial setup known as Eagles Court. It was an effort to deter disorder by delivering quick justice: minor offenses were processed right under the stands, penalties handed down immediately, and offenders removed before scenes escalated. The basement itself, with its sparse concrete rooms and holding cells, became a vivid piece of Vet lore—part practical law enforcement and part urban legend. Former judge Seamus McCaffery recalled descending into that basement courtroom to adjudicate cases, which gave the stadium an almost surreal behind-the-scenes character.

Historic moments and non-baseball events

The Vet played host to a wide range of major moments beyond regular sports schedules. It staged All-Star Games and playoff drama for both baseball and football. It was also a stage for giant cultural and civic events. In October 1979 Pope John Paul II celebrated Mass in Philadelphia during his U.S. visit, drawing massive crowds to the region and contributing to the era’s sense that South Philly was capable of handling events on a global scale. The stadium also held major concerts, soccer and rugby matches, college football spectacles including the Army-Navy game for many years, and moments of political and civic significance. Those events reinforced the Vet’s role as a civic amphitheater where, for better or worse, Philadelphians gathered as a city.

The Vet’s concrete bowl and cavernous upper decks created an atmosphere that was at times electric and at other times was a little cold. Fans in the highest sections were famously distant from the action. The scoreboard complex was ambitious for its time, but the stadium’s aesthetics—vast gray concrete and stacked seating—left many feeling the building prioritized scale and utility over fan comfort. Player complaints about the playing surface and the stadium’s amenities dogged it for decades. It was a place that inspired fierce loyalty from its supporters while also drawing repeated criticism from players, visiting teams, and the media.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, the era of the multipurpose concrete stadium was over. Teams and fans wanted baseball-only parks with intimate sightlines and modern amenities. Citizens Bank Park and Lincoln Financial Field were planned to replace the older venues, and the Phillies and Eagles moved out in the early 2000s. Veterans Stadium closed in 2003. On March 21, 2004 the concrete giant was demolished by implosion in a process that lasted only about a minute but had been years in the making. Residents and fans lined nearby streets to watch the controlled blast that turned a storied pile of reinforced concrete and steel into a jagged heap. The implosion was both spectacle and symbol: an efficient, dramatic ending to a stadium that had been a fixture for three decades.

Today, the Vet lives on in memory and in stories. For some it was the place of youthful Sundays and iconic home runs. For others it represented the highs and lows of urban planning, civic spending, and changing tastes in stadium design. Its basement courtroom, the rough turf, and the implosion are recurring details in how people remember the place. In the end, Veterans Stadium says a lot about its era: big civic ambitions, the appetite for multipurpose modernism, and the reality that architecture meant to serve everything sometimes satisfied nothing completely. Even gone, the Vet remains a powerful chapter in Philadelphia’s sports and civic history.

Please scroll down to comment on this story or to give it a rating. We appreciate your feedback!

Disclaimer: Some of the products featured or linked on this website may generate income for Philly Baseball News through affiliate commissions, sponsorships, or direct sales. We only promote items we believe in, but please assume that PBN may earn a cut from qualifying purchases that you make using a link on this site.

Privacy Policy | Contact us

© 2025 LV Sports Media. All rights reserved.